The invention of recorded music opened up new areas of experience for humankind. Music & memory are deeply linked and give us a form of immortality. With the very same device you’re using to read this article, you could, if you wished, listen to just about any music ever made, we all live with electric ghosts of the past and take it for granted. Music & memory are forever linked in our psyche.

Be it a madrigal with your morning coffee or Belgian Gabba with your GHB the chances are you use music to tune your conscious existence. We all do. To motivate or relax. Celebrate the best days of our lives. Try to find meaning after a breakup. The function of music in our lives is somewhat analogous to that of both medicinal and illicit drugs. We get high from music.

Is Music a Drug?

Some medical experts think so. Or more precisely they observe that music has a lot of the same effects on the body as conventional medicines.

Here’s a quick list

- Music and drugs both create pleasure by acting on the brain’s opioid system.

- Singing can release endorphins, which many drugs do as well.

- Many drugs, like prescriptions, can dull pain. Music has also been shown to provide a sense of relief in stressful or painful situations like surgeries.

Certain Ratios

There’s something about the way that tickling our ear drums with these precise patterns of difference in air pressure just rubs us up the right way. We are incredibly acutely tuned to even the tiniest differences in the ratios between all these different waves. The differences between these patterns over time floods through our brain triggering all kinds of connections.

We feel pleasure, a dopamine release, that great feeling when the DJ, be it radio or club plays exactly the tune you needed to hear at that exact moment? That’s dopamine. The same chemical that is behind just about every form of addiction is also triggered by music.

Music & Memory

But further than that music is almost inseparable from the formation of your memories. Memory & music intertwine during development. Even those with absolutely no interest in music may hear the hits of their youth and have memories come back. At the other end of the scale musicians of all kinds have spent countless hours developing the relationship between their ear and motor skills. The music you share your life with becomes entwined in your brain´s architecture, the roots so deep that even late stage sufferers of Alzheimer’s are often brought to tears by the music of their youth.

Every recording is a snapshot of history that connects us with the past.

As a music lover yourself you no doubt know how deeply the sheer sound of a piece of music can affect you. We often forget that we are in the first part of a very short fraction of history in which it has been possible to actually replicate sound. Sound after all is ephemeral, it is made and is absorbed into it’s surroundings at most seconds after the initial strum, strike or blow. The ability to record it in some manner, codify it, made it outside of time.

It was made immortal by Thomas Edison, and the first time he fired up his device which transferred the vibrations in the air to a wax cylinder he made sound a thing which now no longer always died. He opened up an epoch where sound could be replayed, distribute and dissected in various ways.

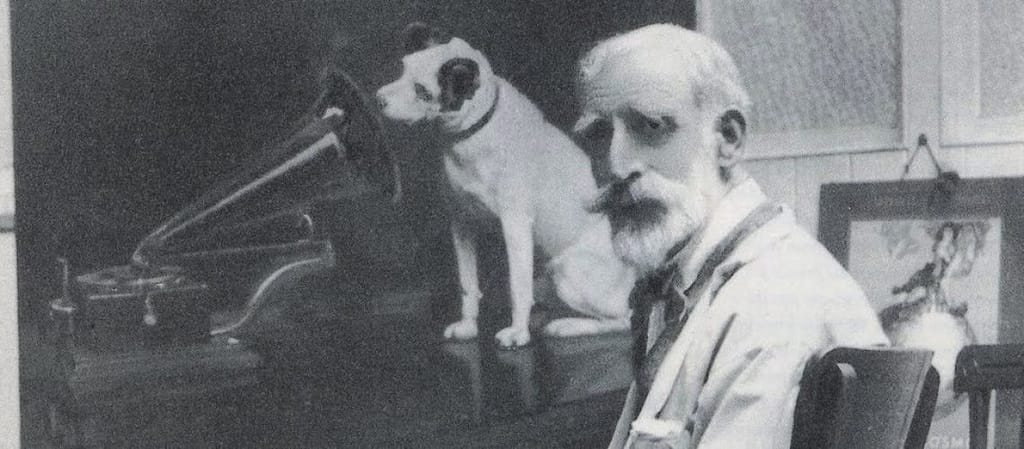

Nipper, the image of Music & Memory

Thomas Edison said that his phonograph would annihilate time and space. Bottle up the mere utterances of man. It was the first time a human voice was recorded. Edison’s business plan at the time didn’t really take music into account. He wanted to preserve for posterity the voices of the great and good of the day. As well of course to sell this amazing innovation.

It wasn´t only the great and good who felt their voices worth preserving and one person who bought and used Edison’s invention in the 1880s was a Liverpudlian theatrical set designer named Mark Barraud. Much in the same way as his modern contemporary may buy a top of the range tablet. It’s not known what he recorded but he no doubt did so in front of a coal fire with his dog laid asleep and perhaps a glass of port.

Not long afterwards, as was not really unusual in Victorian times, he passed away. He left his worldly possessions to his brother Francis, a painter. Francis set to inspecting this new fangled apparatus that his brother had spent so much money on. He would have placed the Wax cylinder on it’s spinet in accordance with the instructions. After that he would have heard listen to the voice of his now deceased brother.

As Francis was listening to his departed brother he noticed that Mark’s trusty Jack Terrier ‘Nipper’ would sit up. Dogs are highly attuned to recognising the very individual characteristics of speech, if not the actual words and meaning. They too can differentiate between different voices. Their brains are wired to interpret the very particular set of rhythms and sounds that make up or speech. The way we breath and the shape of our mouth all. Whether we project from our chest, throat or mouth. Where we grew up. All of these things form the fingerprint of our auditory identity. That which other’s know us by. Nipper would stare intently at the source of his master’s voice.

Moved and inspired, he painted this image. He soon sold it to what was then known as ‘The Gramophone Company’ but who a few years later in 1907 changed their name to the picture´s title.

The logo later got taken up by the RCA company in America and later as JVC in Japan so in a way Edison´s invention gave Mark Barraud a different kind of immortality to that that Edison’s machine granted. Only later was the potential of how music also could be recorded explored , disembodied from it´s context like Edison´s voice cylinders. Mark Barraud achieved a very singular sort of immortality.

The image lives on as a totem of music & memory. The dutiful Jack Russell listening to his departed owner

From this point on all of us started to have two lives. Our biological lifespan and our media lifespan, our media lifespan is for how long physical evidence of our sheer existence lives on. Take for example Robert Johnson, a man who only a couple of photographs exist of. He sat down in front of a machine not too dissimilar to Edison’s. It made him one of the most important and influential musicians of the twentieth century.

A Sea Change in Human Experience

At the beginning of the century the acts of making and listening to music were physically tied together. It’s appreciation was only made possible by being in the same room as a vibrating column of air manipulated by skilful hands. This changed with the coming of radio and and records, now music could be heard most anywhere. It could be endlessly replicated distributed and replayed. More than that though the ways that music was created changed drastically.

As the century progressed people started using and abusing innovations to their own ends. To be in the presence of fine musicians was once a luxury preserved only for the upper classes, but the 20th century democratised music, for not just for listening to music but also for making it. The two have fed off each other throughout this odd evolutionary leap we have taken since Edison first fired up his invention.

Often the technical advances and the story of the players in this story are intertwined with the terrible conflict which afflicted the last century. Some professions which were integral to military defence also turned out to be pretty useful in the manipulation of sound. When peacetime came this expertise and technology remained and found all kinds of outlet in every field. Conflict opened up the labour market for women especially in organisations like the BBC to work in creative roles. But our story doesn’t start and end at all with the recording of sound, we’ll be looking too at how human’s have utilized innovations in technology in numerous ways. We´ll see as well that people have been thinking about these things for a lot longer than you might imagine.

It’s the story of how, certain individuals looked for new ways to produce sound and to think about the world and how we experience it. Our story is about those who expanded the parameters of what possible. Very often the people we will be talking about wanted to get rid of all the rules and conventions that they saw in music. Members of the French resistance learning to bend time through using tape. Others generate whole new sounds never before heard using repurposed military equipment. New methods require new ways of thinking and people have adapted to the myriad possibilities offered in as many ways as possible.

All instruments allow players to express themselves through movement or customisation but electric and as we go later into the story electronic ones allow many more numerous opportunities to do so. In a Lester Bangs interview Kraftwerk described their synthesisers as being ‘acoustic mirrors’, part of the menschmachine. Just as Jazz takes a theme and re-harmonises it to create any number of results individuals all over the world adapted and worked with what they had.

Music & memory have evolved together over the last century. We now have sounds imprinted upon our brains which could never have existed before.