What is Krautrock AKA Kosmische Musik? A precise definition is impossible. The endless shifting rhythms of CAN are a world away from the proto-techno of Kraftwerk. The industrial Dada of Faust is very different to the plainsong reveries of Popol Vuh or the ambient waves of Tangerine Dream. And that’s without mentioning NEU! who perfected the motorik beat (ably assisted by Conny Plank). There’s a lot of diverse music to hear. It could be that you want to know what the best Krautrock Albums are. Maybe the best Krautrock bands. Perhaps you’re looking for a copy of Krautrocksampler, Julian Cope‘s great but highly subjective book on the subject.

In this article I'll be talking about some of the factors and circumstances that went towards creating what we now call Krautrock. To guide you on your way there's a Spotify playlist, link here if the embedded player doesn't work on your browser. I'll be following this article up with 30 of what I think are the best Krautrock albums, split into sets of six, chronological. So think of this as part one of a six part article. The playlist is mainly one track from each album.

The ‘What is Krautrock?’ Playlist

Where did it come from?

It was born out of circumstance. The history of Germany in the 20th century is to say the least complex. The nation itself was almost destroyed by the second world war. Equally important was the psychological effect this had on the children who would grow to form the counter-culture.

“I grew up in these total ruins. That was an experience that is still deeply within me: growing up in this town, this land, where everything was devastated, all the buildings, all the culture.”

Irmin Schmidt, CAN

The Marshall Plan

The nation was split into two parts, like a mass experiment. After that initial devastation the western side underwent an economic miracle. It was prosperous, and highly organised. This was ‘big state’ capitalism. Of course this organisation was not all due to the famous Teutonic rigour. Strictures had been placed upon German society by the allies after the war.

The aim of this was to create a prosperous middle class to prevent a revival of populist politics. And it worked. Massive international companies like Volkswagen, BASF and Beyer brought prosperity. Thus, Germany was, in political and financial terms, a success.

It was an ethos embodied (and at times satirised by) by Kraftwerk. They made a series of albums themed around different aspects of modern life (radioactivity, the car, the train, the computer). They also created a lot of the sound palette for electronic music from that time forward. But we’re getting ahead of ourselves.

What Music influenced Krautrock?

Rock

Musicians from what became later known as Krautrock were greatly influenced by the avant-garde, be that rock, jazz or electronic music. In rock a festival appearance by Frank Zappa’s Mothers of Invention sent shockwaves. The Velvet Underground records were also highly influential (that pounding ‘motorik beat’ is not so far away from what Moe Tucker was doing at her kit).

In a famous Lester Bangs interview Kraftwerk declared themselves fans of ‘the Heavy Metal music of Detroit, the MC5, The Stooges‘. This was before the term ‘heavy metal’ became formalised.

Free Jazz

Free Jazz, another wild noise was relatively popular in Germany in the mid 1960s. Jaki Liebezeit of CAN was for a time Germany’s leading free jazz drummer. Irmin Schmidt recalls loving the violence of John Coltrane‘s later music. This sense of expressionistic freedom can be heard in the music of many of the best krautrock bands.

Avant-Garde Electronic music

Schmidt and bandmate Holger Czukay both studied under Karlheinz Stockhausen. He was probably the most famous avant-garde composer of his day. His was a dry clinical approach to working with sound. He carved and grafted tapes, used electronics, human elements and chance. His experimental working methods went on to influence a lot of the best Krautrock records, not just those of CAN.

A Very Irregular (tape) Head

Syd Barrett and the early Pink Floyd were another touchstone influence. Barrett generated waves of vibration using his guitar and echo units. Tape loops and circuitry. This technique of painting with echoes became a building block of ‘Kosmische Musik’.

The common thread in all this music is that it showed that things could be different. Different to the commercial pop music fed to the masses. More than just another product.

As for music being made in Germany at the time there was nothing really to inspire a new generation. Well, apart from one band.

The Monks

The Monks were a true oddity. Ex-US servicemen who stayed in Germany after their tours of duty. The Monks were an unruly garage band with an amped up intensity. They got to be pretty popular in Germany or at least their unconventional haircuts got them attention.

Though the compositions had their roots in Detroit Soul and Garage The Monks used repetition, fuzz and feedback in their songs. At least some of those who would go on to form bands over the next years were listening.

A generation looking for a voice.

There was a conscious attempt amongst the majority of the movement to disavow blues and soul clichés. This was a generation that needed to find it’s own voice. Not Americanised and bland. Also it needed to be created from nothing. The German culture had been destroyed. The very concept of national identity had been tainted. New forms needed to be created, forms that didn’t draw on a shameful history.

What the bands who are called Krautrock have in common is not so much musical elements as a unity of opposition to the German mainstream. The mainstream in terms of commerciality, imported American and British pop music. Homegrown music was almost all ‘Schlager’ (which translates to ‘pop’ music) the kind of songs that got and still do get entered into Eurovision.

The Children of a Country in Denial.

The name of the rules placed on Germany was ‘The Marshall Plan’. It didn’t prevent teachers from telling their students about the horrors of the second world war. But that doesn’t mean they did. They certainly didn’t tell of their and their students’ parents’ complacency. And neither did the parents. The past was a closed book.

Of course the secret got out. Through the younger generation there was a wave of growing unrest and disgust. Like a lot of Europe in 1968 there were widespread protests. Hair got longer, people dropped out, they got angry and involved.

What could be broadly called left-wing anarchism became popular. This meant people living in communal housing, starting their own art spaces, joining protests and sit-ins. It was from this milieu that the bands of this time came. Even playing in a band to an audience was a political act.

A Restrictive Society

In West Germany at that time all work was arranged through a government agency. This was all well and good for factory employees but meant that local musicians had little opportunity. It was effectively a crime to form a band and do a gig in a bar without the proper paperwork

This further placed musicians outside of the mainstream. If there was no need to learn top 20 hits for a beer hall why be commercial? This meant that German musicians didn’t have the same vocabulary of blues and soul ‘chops’ as in Britain, the USA or even behind the Iron Curtain. They developed their own style in isolation.

One arm of a movement.

A hint of the intertwining of music, the arts, and revolutionary rhetoric lies in the meaning of the name CAN. It’s an acronym for ‘Communism, Anarchism, Nihilism’. Another is how Amon Düül first lived as a commune then split off into two ideological factions. Amon Düül 2 later had the infamous Red Army Faction (the Baader-Meinhof terrorist group) as unwanted houseguests.

There was a new wave of German Filmmakers too. CAN had music included in films during their early days. Werner Von Fassbender had friendships with many musicians of the day. It was said he could not work without a Kraftwerk record playing. Amon Düül 2 appeared in Fassbender’s early film The Niklashausen Journey (Or to give it its hilarious German title Die Niklashauser Fart). Florian Fricke of Popol Vuh enjoyed a long and celebrated creative partnership with the director Werner Herzog.

German rock evolved in a set of arty, revolutionary bubbles. It was influenced by different kinds of art.

So what is Krautrock musically speaking?

Each band is different of course and different cities had different scenes. I’ll be covering some of the specifics in upcoming articles. In the meantime here is a summation of what Krautrock is in musical terms. Very generally speaking the music itself tends to have the following elements:

Repetitive, often hypnotic, rhythms which avoid rock, jazz and pop cliches. Very often this takes the form of a pounding beat commonly known as ‘Motorik’.

Unconventional song structures. The concepts of verse and chorus are usually ignored. Often recordings are based on long jamming sessions. It’s not unusual for tracks to take up a whole side of a vinyl record.

A lot of times tracks are fractured, moving through different sections. This was done through tape editing. Which leads nicely to…

Heavy use of effects and studio manipulation. As I’ve already noted early Pink Floyd were a key influence on Krautrock and Kosmische Musik. The abstract spaces created through echo and delay were formative for the movement. Producers like the great Conny Plank picked up the baton from psychedelia production wise. They created new and surreal sound worlds.

Seizing the Means of Noise Production.

German musicians were enthusiastic early adopters of all kinds of new equipment. Germany was a very technologically advanced country. Consequently, musicians had a wider range of choice. Synthesisers, echo units, and all manner of gadgets were all present and used to excess.

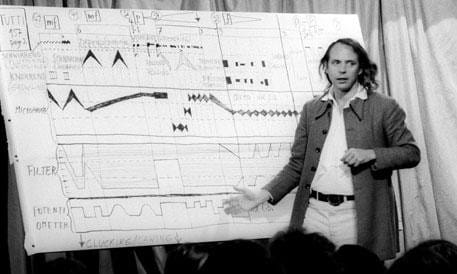

Aside from that anything goes really, which is part of the joy of the genre. Musique Concrete (tape editing and found sounds) are common. Flutes are not unknown. Florian Schneider of Kraftwerk (pictured) played electronically treated flute for many years. German musicians of the time were willing to make music from a palate of instruments quite outside the ‘western norm’.

All of this lead to a very diverse set of records. Asking ‘What is Krautrock?’ is a little like asking ‘What is American music?’. There’s a lot of variation. Much of this variation is between songs by the same artist. Even within the same song.

The music of Germany in the 1970s birthed many different genres. Not just the electronic innovation of Kraftwerk. Much of what came to be called Ambient and New-Age has its roots in the shimmering chasms of Tangerine Dream and Klaus Shulze.

But none of this was originally called ‘Krautrock’ though. At least not at first. It’s an anglophone confection, retroactively applied . The name didn’t exist. This was, if anything, ‘Kosmiche Musik’ (Cosmic Music).

Where did the name Krautrock come from?

One aftershock of the second world war was that the British felt a need to ridicule German culture at any available opportunity. Usually this manifested in sitcoms or caricatures. As a result it was pretty much impossible for most English journalists to take the new music coming out of Germany seriously. And so they dubbed it ‘Krautrock’, a mildly racist allusion and a call-back to wartime slurs.

The majority of german musicians of the time hated the name. Individual germans have assured me that they do not find the term offensive. In any case, the name stuck and here we are.

A Faustian Pact

Some embraced it though, particularly Faust. They playfully took the slur as the title of the first track of their fourth album. The British Label Virgin funded this. They had made big bucks from Mike Oldfield’s ‘Tubular bells’ and were spending money on anything experimental which might appeal to freaks. As a hippy/head hang-out Virgin record shops have a special place in 70s music history.

And in that track is as good as a summation of the ethos of Krautrock as you could ask for. It starts with a swirling echoic drone. It’s not really clear what instrument we’re listening to. This is music not too far away from the minimalism of Philip Glass or Terry Riley. It’s a pre echo of some of the sounds that Kevin Shields would bring to My Bloody Valentine’s records 15 years later.

This state of affairs builds slowly over a few minutes. Almost begging you to hit the skip button before you begin the song. A tambourine builds and in the meantime shards of distorted guitar and electronic noise bounce off each other.

Faust but Slow

Eventually at the 7 minute the entrance of the drums is shocking. Compared to most of the Genre the opening drum fill is like Buddy Rich. It puts the preceding few minutes in a different context completely.

It’s the quintissential Krautrock track in many ways and kind of a test to see if the genre fits for you. Faust are not my favourite of the bands of that era (that would be CAN). But if you can’t take something from this track then I’m afraid, my friend Krautrock is just not for you.

How Krautrock caught on in other countries.

Probably the main influence on exposing the movement to British ears was the late DJ John Peel. His omnivorous approach to music led to regular plays for many of the best known names. Indeed, after a slow start this new German rock found its way to many who would become influential (the young John Lydon and Mark E Smith being just two). Other musicians who fell under the spell of this music came to include Brian Eno and, a little later, David Bowie.

As previously stated I’ll be following this article up with a series on the best Krautrock albums. I’ll be doing these in chronological order in sets of six.

In the meantime if you’re eager to learn me I would definitely suggest you buy David Stubbs excellent book ‘Future Days’. In fact, I’d say that it’s essential reading. Stubbs knows his subject inside out and lays out the different scenes that made up the whole excellently. Likewise Rob Young’s excellent history of CAN ‘All Gates Open’ is highly recommended. I found valuable information for this article in David Buckley’s ‘Kraftwerk Publikation’.

Julian Cope’s Krautrocksampler is great and most importantly, the work of an enthusiast. It’s an important book because Cope’s evangelising has played no small part in the genre’s popularity. However, it possibly suffers from having an unreliable narrator, research done before the internet age and idiosyncratic choices. He seems like a real one though and long may he reign.

‘What is Krautrock?’ Bonus Beats

Completely separate to all what was going on in Germany a group called Pärson Sound were making a correspondingly intense racket in Swedish art galleries.

A few of their performances were taped. Here’s ‘Tio Minuter’. They sound uncannily like assorted Kosmische alumni jamming. Lets put it down to morphic resonance.

Bonus Bonus Beats

Not every German Pop/Rock hit of the era was a dud. For my money The Rattles earned their place at the table with their single ‘The Witch’. It’s definitely not Krautrock. Great use of the ‘Bo Diddley’ beat, Groundhogs style guitar and Tony Visconti style strings though.

Bonus Bonus Bonus Beats

Staying on a horror theme here is the utterly bizarre novelty album ‘The Vampires of Dartmoor’. Now highly prized amongst vinyl collectors. Mainly for this track which is chock full of potential samples.

Bonus Bonus Bonus Bonus Beats

Germany’s most famous and successful musician of this era was James Last. He was an easy listening bandleader. He has one album that’s prized amongst people who collect records. It’s called ‘Voodoo Party’ and contain’s the insane ‘Mr. Giant Man’.

A Shameless Plug

Finally, I also make music, sometimes very Krautrock influenced. Here’s two of me jamming to a Motorik beat and the Krautrock trope of the autobahn.

You can like subscribe and all that business or sign up to my email list where I’ll only send notifications about new articles, no unsolicited spam. In the meantime if you’ve enjoyed this article and are a very generous person please consider buying me a coffee via the widget in the bottom right corner or the QR code on my contact page. Sharing is caring too, use the links above.